What you need to know to create professional video subtitles

The most common rules for subtitles are the Advanced Television Systems Committee (ATSC) standards, or the BBC or Netflix’s subtitle rules.

Here are some of the most basic criteria to keep in mind:

- Characters per line (CPL): 37-40 characters including spaces and breaks per line. A subtitle should have no more than 2 lines. This is to make sure the subtitles are not too long and cover the frame. In addition, the length of a subtitle line depends on the dimensions of the video, i.e. CPL to broadcast on television and phone has its own requirements, but not longer than 68% of the width for a 16:9 video and 90% of the width of a 4:3 video.

- Characters per second (CPS) is an important factor to ensure that viewers can both read the subtitles and follow the content. 20 characters per second is the ideal number, and is highly recommended.

- On-screen caption (OSC): to display captions from the translator, not by the speaker, on the screen. However, the addition of footnotes should be limited of to avoid distractions. The information on the screen that needs to be supplemented is information about the speaker, about the event, the situation, or the text, etc. Information such as numbers, dates, or store names, trademarks, etc., if not relevant to the content, or otherwise unaffected by the content, may be omitted. Subtitles for text displayed on the screen may overlap with the speaker’s voice subtitles, but avoid overlapping more than 2 subtitles.

- Font size, font type, font color: According to customer’s request, but mostly white, black border or black background. The redundancy of the black background should not exceed 0.5 cm and the font size should not exceed 8% of the width of the video.

Create and edit video subtitles

The unchanging rule when creating subtitles is that the start and end match the speaker’s words. Avoid letting the speaker not finish speaking but the subtitles have ended, or vice versa. This is all because of the viewer’s ability to read subtitles and view images.

- Skip stumbling blocks and mistakes.

- The paragraphs where the speaker pauses will be split into a new sentence or only continue the sentence when the sentence idea is followed.

- Words that can be easily read should not be eliminated.

- Try to form a single sentence, avoid in a two-sentence subtitle.

Subtitle duration (timing):

The unchanging rule when creating subtitles is that the start and end match the dialogue, sometimes the song or the cry. Avoid leaving the dialogue unfinished without the subtitles ending, or vice versa.

But the truth is not that simple.

The duration for a subtitle should be 160-180 words/minute or 0.33-0375 words/second. However, depending on the video content and audience, this duration may vary:

Prolonged:

- When there is important information, long number (for example: 15,546) or the speaker’s speaking rate slows down

- When many people talk at the same time

- When there are many events happening on the video, like football match, map, etc.

- When appearing specialized words, strange words.

Shorten:

- When the scene cuts suddenly

- When chanting slogans

- When you can read from speaker’s mouth

- When information is repeated, brief.

However, the duration for a subtitle must not exceed 10 seconds, which could distract the viewer because the subtitle sentence is too long (except for the information on the screen).

When there is a dialogue, it should be presented in bullet form and the dialogue should not exceed 3 seconds. If the dialogue’s speakers are unknown or not showing faces, the speaker’s name/gender can be written in front of the line in the dialogue.

Subtitle location:

Usually do not take up too much space for a frame.

- Center position below frame: This is the most popular position, it is easy to stretch the length without affecting the image of the video

- Center position above the frame: When setting subtitles in this position, i.e. (1) in the video there are two subtitles in two different languages, (2) the video is showing information that occupies the entire lower part of the frame, (3) the video is showing the important image in the bottom corner

- Lower left/right corner position: Subtitles must be placed at the opposite corner of the information displayed on the screen, avoid placing subtitles above the frame.

How to break the subtitle line

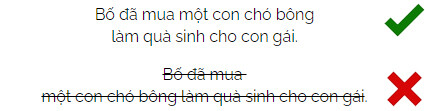

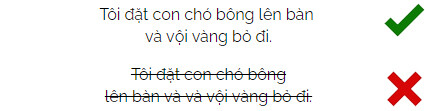

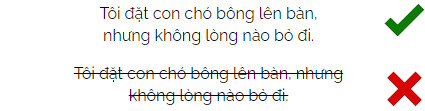

Subtitle line breaks are often ignored when subtitle creators focus too much on the above 40-CPL criterion, leading to mercilessly and painfully broken sentences. Subtitles are usually broken, but not limited to, in the following ways:

Object:

Prepositions and next action:

Linking words, punctuation marks and subject phrases:

Proper names and verbs:

Subtitles and subtitle translation

Subtitles are often associated with the translation of movies and entertainment programs, but subtitling is much more extensive. Many legal, judicial, medical, scientific, technical, advertising, and religious videos require subtitles to preserve the original language while ensuring the multilingualism of the video.

In addition, there is now parallel subtitle translation for digital broadcasts. The reason for this demand is because (1) broadcasts on digital platforms often have a large audience and are mainly via electronic devices, that is, there is no dedicated equipment for parallel interpretation, ( 2) viewers focus a lot on the broadcast content itself, i.e. want to receive the content in its original form, without mixing other languages, (3) the speed of updating content is dizzying. Broadcasts often attract a lot of viewers in real time. The subtitled version will certainly be updated after the broadcast, but then the content is outdated and viewers often revisit it later because there is a need for the language, not the content.

Although subtitles appear slower and have many limitations, they have initially opened a new era for subtitle translation: subtitles can be provided side-by-side with the speaker as side-by-side interpreters of equal quality. But side-by-side subtitle translation is different from machine translation. Machine translators only provide near-instant translation when content is available, while live broadcasts provide no prior, even unpredictable content.

Conclusions

With the current state of chaotic and self-directed subtitle translation, it is necessary to set a standard for subtitle presentation in Vietnam. Although there is a separate censorship panel from broadcasters or agencies that specialize in content moderation, there is still no censorship system for the presentation of subtitles. In addition, subtitles need new software and technologies developed to make subtitles provided in real time a dream come true.